There are a plethora of blog posts and articles across the Internet dealing with the age-old conflict of responsibility without authority. This short LinkedIn post even cites a fun term “NAG Syndrome”, so named because the responsible person without authority inevitably resorts to nagging to try and get things done. In this post I offer a theory for the root cause of this situation for PMs, absolve (some) companies of blame and offer some ideas to lessen the pain for all.

The dysfunctional project lifecycle

In my project management roles this was a daily struggle and probably my biggest stressor. The typical scenario is:

- PM works with team to come up with realistic estimates for work and a project plan.

- Plan and time estimates are provided to client along with other client expectations.

- Work begins.

- Work starts to run late.

- PM speaks w/ engineers who report various reasons for lateness. The reasons range from conflicting work from other projects to being redirected to production support issues to unforeseen obstacles.

- PM works to overcome obstacles and adjusts schedule.

- Work continues to run late due to similar issues.

- PM speaks with functional engineering manager. Engineering manager is sympathetic and tries to be helpful. Some understanding is reached to try and keep things on track.

- PM adjust schedule.

- Work continues to run late due to similar issues.

- PM wrestles with whether to go over head of engineering functional manager.

- PM escalates up the chain. Changes are made to either resources, processes or both. Account management gets involved and tries to smooth things over with client.

- Work continues to run late due to same issues.

What I omitted was that in between all these bullets, the client and upper management are having a lot of difficult conversations with the PM and giving them negative feedback. The PM is ultimately held accountable for the project delivery. The PM eventually has to nag and constantly monitor the engineers on the project to try and ensure they’re fulfilling their commitments.

It’s the org structure stupid!

I think this type of situation is probably more prevalent in smaller organizations. I say that because the root cause of this is an organizational structure typical to smaller companies, specifically when project resources do not report to the PM. Time for a quick review of org structures.

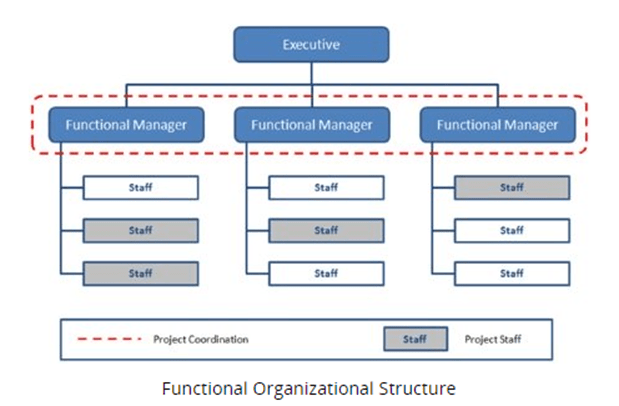

In the traditional functional structure, the organization is split up into departments based on business function. The staff report to functional managers, who in turn report to middle / upper management.

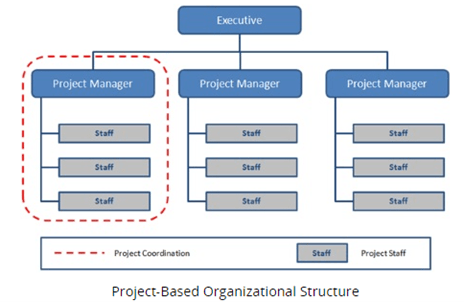

The other end of the spectrum is project-based or, as PMI calls it, projectized. This is the ideal structure for an organization whose business revolves around executing projects, i.e. a service provider. Instead of being aligned around functional departments, the staff are assigned to projects managed by a project manager. The PM has control of resources including staff and budget.

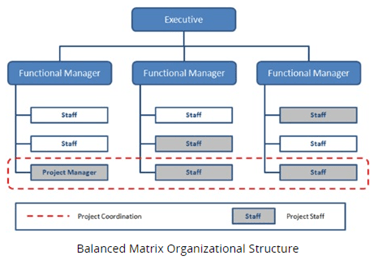

In between is the matrix structure, of which there are several levels. The term matrix implies dual reporting relationships. Staff have a functional manager and there are project managers. The balance of authority between the two determines the flavor of matrix.

Here’s what a balanced matrix looks like as an org chart.

The problem occurs when a project-driven organization uses a matrix structure, particularly a weak or balanced matrix, rather than a projectized structure. The PM will not have authority proportionate to their responsibility for onboarding revenue.

Why, oh why, does this happen?

So why does this happen particularly with smaller companies? I believe there’s a good reason for it and it’s not due to any fault of their own.

If you look at the project-based structure, you see each staff member is assigned to one project with one project manager. This is ideal (and indeed important in agile scrum). However smaller service providers tend to work on many smallish projects. Indeed, the IT projects I led were typically tens to hundreds of hours of work. And I was managing around 15 – 20 at a time. When you have < 10 engineers and you’re spreading them among 50+ small projects, do the math. You can’t have dedicated project teams. You end up with PMs and engineers spread across many projects. And projects turn over on a week-to-week basis. If you had the engineers reporting to PMs in this type of business, each one would end up reporting to all the PMs simultaneously. That’s a bit hard to manage for a small business and it’s not scalable.

In a larger company with a greater number of resources working on large multi-year projects with huge budgets, you can dedicate a team to a single project full time. Then you’re in a position to align to a projectized structure.

So it’s really not the company’s fault?

If you’re a PM working for a large company managing large projects and you don’t have authority over staff and budget, I believe there is misalignment in the organization. If, however we are talking about a company of say 200 or fewer employees, then no I don’t think it is their fault. Don’t get me wrong, there is plenty of chaos and dysfunction rampant in small companies, especially young small companies. It’s part of the game. But as far as the issue at hand, it’s a chicken and egg scenario. You can’t evolve into a project-based org alignment until you can have dedicated project teams, or at least something close. And you can’t have dedicated project teams unless you are working on sufficiently large projects and you have enough staff. So the book of business has to grow and you need to chase bigger fish. That is easier said than done and may not even be a long-term business objective for the company.

Then what is to be done?

As a manager, both PM and functional, I always like team members who not only point out problems but offer ideas. I will admit that even when I was in a PMO management role at a small service provider I could not crack this particular nut. But I did nibble around the edges. Here are some ideas based on my experiences.

1. Provide PMs with avenues for healthy communication.

I worked for one organization where we had a weekly portfolio review meeting w/ representatives from account mgmt., accounting, the engineering functional manager, project engineers and the COO along with PMs. It was an “expensive meeting”, but it allowed the PMO to broadcast the health of all our projects to all key internal stakeholders at once. We focused our time on issues and roadblocks. It created some real efficiencies in getting much needed help and forced the occasional uncomfortable but necessary conversation out into the open.

2. Leverage an information system for collaborative resource scheduling.

In a matrix organization resource scheduling for projects should be a collaborative exercise between the PMs and functional managers. Ensure that all resource allocations are input into an information system for tracking and reporting. Scheduling (and re-scheduling) should occur on a weekly basis, preferably a few weeks out. Ensure the PMs and functional managers review actual variances together on a weekly basis.

3. Make functional managers share in responsibility for project delivery.

Once you’re keeping track of scheduled to actual work data, the functional manager should need to answer for the shortfalls in actual work done – not the project manager and not the project resource. Although the project resource needs to answer to their functional manager.

4. “Stick” resources to a particular PM.

If you have an engineer who specializes in VoIP, pair them up with a particular PM on your VoIP projects. The larger the proportion of that engineer’s work is for a single project manager, the easier you’re making it to juggle their scheduling. The more you’re able to stick resources to a particular PM, the closer you’re getting to a projectized alignment. Plus you will gain tangible efficiencies from the rapport they develop from working together so much. There is some risk around cross-training, etc. when you do this.

5. Keep project resources out of production support.

I know this is hard to do if you’re a small business. But until you have separate teams for these functions, you will be operating in a state of chaos. Not organized chaos, which I will take in a small business, but unadulterated chaos. Once you do have separate teams, put in some process and procedure to try and keep them separate. If you can do this 80% right, give yourself a pat on the back.

And that is all I’ve got. Good luck out there PMs!